An engineer’s pet peeve: how we pump water to our houses

3 min readI have a childhood memory of travelling to my village from the city, a three-hour journey that would rattle your bones as the jeep wrestled with the bumpy roads. We would grow hopeful that the journey over as the sight of overhead tanks appeared in cities we passed.

Local municipalities used to have a “darogha” man whose main job was to distribute and recover water bills. He would fine people if their water tanks overflowed if the football valves malfunctioned.

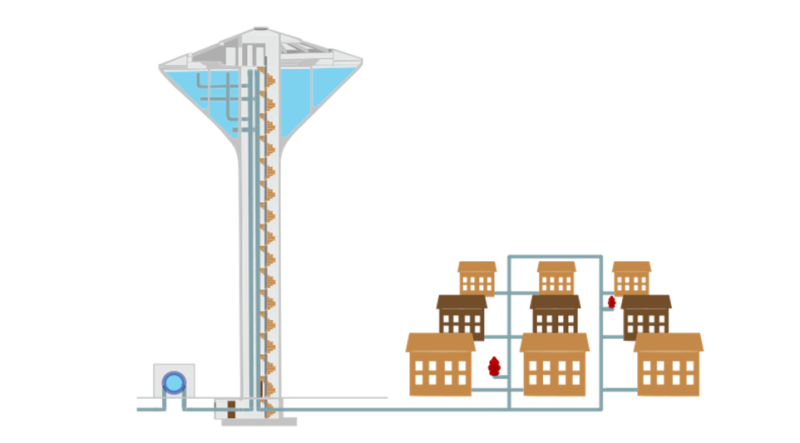

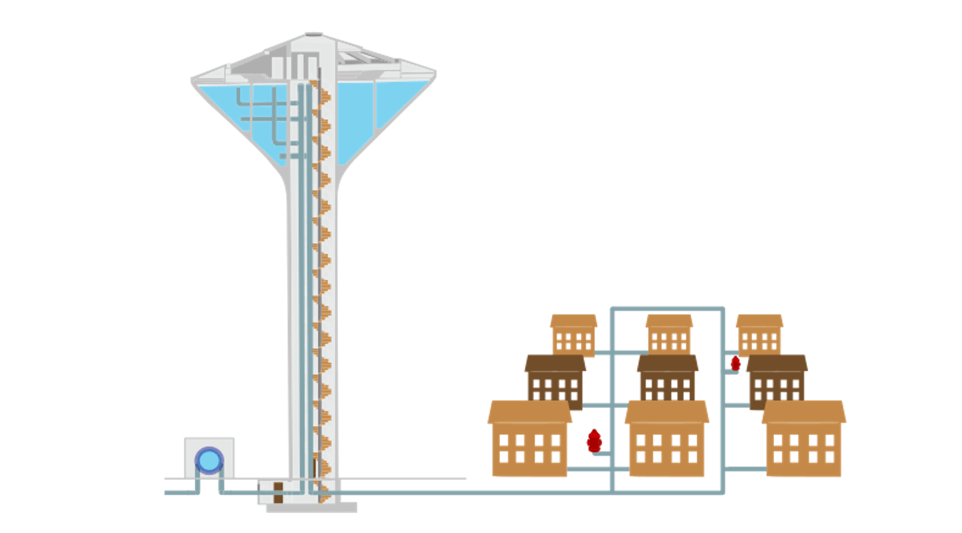

This system used to rely on the magic of gravity. The water was stored in an underground tank so its sediment got time to settle (although in those days not that much raw factory and household waste was dumped into rivers or canals). The water would then be pumped from the underground to an overhead tank that sat higher than the level of the house tanks. Its master valve would be opened so the water would flow down to everyone’s houses and a football valve would turn it off automatically, so that everyone got a share.

This single pumping system was basic hydraulic engineering design. It factored in how much water was available, what each person needed, the height and size of the main tanks and capacity of the water lines.

Our cities still use such engineering but some of its really efficient methods have been long done away with.

Take the example of a small housing society with 200 average-size houses. A heavy-duty pumping machine sends its water to the colony’s underground tank. At some places it takes two or three stages of pumping to get it there. The water will be stored here for 24 hours.

A pump will push this water into the housing society distribution system. The houses will each have suction pumps (called dogdogi motors or donkey pumps) attached to their underground tanks which will be pulling the water into these micro-reservoirs. Another motor (rotary pump) will pump the stored water up to the house’s rooftop tank.

For an energy deficient country, that’s a lot of fuel being spent to get water from one place to another.

If the electricity goes out at this housing society, and pumped flows are interrupted, vacuums will develop in the running dogdogi pumps for the 200 houses. A vacuum weakens pipe joints that then start to leak. Along the way sections of the pipeline begin to corrode. Then moisture in the soil is sucked in to the line because of the vacuum pressure. That moisture is invariably contaminated with raw sewage that has leaked from sewage lines which sit close to the water lines. And this is how sewage-laced water reaches the household taps.

This water is then used by people to brush their teeth and wash their spoons. If this seems insignificant, just go through the cost of our disease burden caused by water-borne bacteria and viruses.

I would like to think, however, that I am an optimist. And the way forward is realization. We need to rejuvenate our local government water supply institutions. Then we need them to be staffed by young blood. Every year hundreds of engineering, economics, social sciences students graduate from our universities. They should be engaged in field surveys, data generation, analysis, planning, and designing our systems.

We need a new set of laws for new housing schemes to implement gravity flow conveyance systems for their water supplies. Everyone cannot afford water tankers and especially not in this economy. When I look back at the simple community storage tank, I can’t help but wonder why we abandoned perfectly simple engineering and decided to switch to energy-hungry ways of managing our water.

For the latest news, follow us on Twitter @Aaj_Urdu. We are also on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Comments are closed on this story.