Vaccines, 'Delta strain' bring new pandemic challenge

4 min readBy Peter Apps

In the southern Chinese city of Guangzhou, engineers are building a 5,000-person quarantine facility, central to Beijing's strategy for reopening itself to the outside world while COVID-19 continues.

Having largely stamped out its original outbreak last year, China now claims to be on the edge of shutting down a much smaller outbreak of the Indian-origin “Delta Variant” in Guangdong province. That appears to have also yielded a new broader strategy as China attempts reopening – potentially bringing in all foreigners through that southern region, and in doing so hoping to protect the rest of China.

As the pandemic enters the second half of its second year, almost all countries face the same dilemma: if, how and when to attempt to reopen to the outside world.

It is a challenge made harder by the increased speed at which the Delta variant has spread – not just faster and to more people, but also often infecting those already vaccinated, even if they then become less ill.

For now, the temptation for countries like Britain is to reopen and risk further spread of the new variant, relying on vaccines to prevent a large number of fatalities. The risk, of course, is the emergence of new strains that change that calculus – but for some other nations, the crisis remains acute and in some places continues to worsen.

Globally, some 3 billion people – around 40% of the world’s population – have now received at least one vaccination shot, a colossal achievement in the circumstances. Some countries such as Britain, Israel and most parts of the United States have vaccinated the vast majority of those most vulnerable to the virus.

Others, however, have barely started, and tempers are fraying. COVAX, the UN-backed international scheme aimed at delivering vaccines to poorer countries, has so far delivered only 90 million doses to 132 nations, its rollout severely dented by India’s decision to block vaccine exports in the face of its own catastrophic outbreak.

TEMPERS BOILING OVER

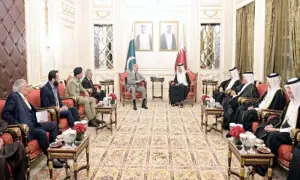

From national economies to individual families, balancing how to control the virus and restore pre-pandemic opportunities is becoming more challenging than ever. On Monday, Pakistani migrant workers stormed a vaccine centre in Islamabad, desperate to obtain doses of the vaccine made by AstraZeneca and Pfizer so they could travel to Saudi Arabia for jobs.

In Australia, which had viewed itself as a COVID-19 success story after sealing its borders and eradicating cases through long lockdowns, cases of the Delta variant spreading out through quarantine centres have caused outbreaks in five of the country’s eight states.

Compared to other Western nations, Australia is well behind in its vaccination programme, with only 5% of the population so far reached and confused official signals on whether the AstraZeneca vaccine should be given to those aged below 60.

Previous advice in Australia has been not to do so over the reported risk of blood clots – but the prospect of a new highly contagious outbreak ripping through the unprotected population has prompted the government to propose offering doctors indemnity for vaccinating those under 60.

Australia and New Zealand are particular outliers, their early success controlling the outbreak now paradoxically keeping them more on edge than ever, struggling for vaccine supplies and unable to reopen without undoing their past efforts. Other states that have previously struggled are now moving forward, with European Union nations now rolling out mass vaccination in ways they struggled to achieve earlier in 2021.

VACCINATING BILLIONS

Crucially for the global picture, India and China are both on the path to mass inoculation. This week, India announced it had now vaccinated more people than the United States, more than 320 million doses. That still leaves more than a billion Indians unprotected, although many may now have had the virus.

In China, where that is almost certainly not the case, Beijing has this year quietly switched focus from using Chinese vaccines as a geopolitical tool for influence overseas to prioritising its domestic population. Last week, China said it had given more than a billion vaccine doses, almost half in the last month, although experts say rollout has been uneven.

In cities such as Shanghai, more than 80% of the population are now thought to be protected, compared to a quarter of that in other regions. With Japan pushing ahead with the delayed summer Olympics this year, Beijing is desperate to be able to hold the Winter Olympics next year – and with enough worries about foreign states boycotting over human rights, those in power will be keen to avoid COVID-19 being another reason to stay away.

Providing no new resistant variants emerge that require revaccination, those numbers should make widescale vaccine exports easier and give real hope that COVAX might genuinely meet its aspiration to deliver 1.8 billion doses in the first quarter of 2022, allowing serious vaccination of vulnerable populations in the poorest states for the first time.

If 2020 was the year that the pandemic changed the world, 2021 is already set to be the year that vaccines revolutionised how the world could tackle that pandemic. To what extent the world returns to normal – or what a new normal looks like – will require new decisions, and we are only just starting to learn what that might look like.

For the latest news, follow us on Twitter @Aaj_Urdu. We are also on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Comments are closed on this story.