What is it about minarets on Ahmadi places of worship?

8 min readHighlights

- An Ahmadi place of worship was attacked in Sargodha on April 16 in the latest outbreak of mob violence

- Two Ahmadi places of worship in Karachi defiled in the span of two weeks

- FIRs against the two places were lodged five months ago

- Hundreds of Ahmadis have been arrested for ‘posing’ as Muslim, says spokesperson

- Khatam-e-Nubuwwat lawyer: Many Ahmadi worship places built on state land allocated for Muslim mosques

In one of Karachi’s busiest neighbourhoods about a dozen men, their faces covered in black masks, gathered in a side street on Thursday afternoon. They were waiting for a signal. Suddenly, at least four of them leapt on to the entrance of an Ahmadi worship place. They swiftly scaled the closed iron gate and in seconds were on the pediment or beam above the gate, which was adorned with four small minarets.

The men smashed hammers into the minarets to bring them down. A policeman deployed in the street below to protect the place of worship of the persecuted community dashed towards the men but was stopped by a man. The policeman pulled out his phone to inform his seniors that another Ahmadi site had been attacked. This attack in Karachi’s Saddar is just the latest in what has been a series of similar incidents across the country, with most taking place in Punjab.

In Karachi, this was the second attack within a span of two weeks. One site was debased on January 18 in Martin Quarters, roughly three kilometers from the Saddar attack.

The Saddar structure with the minarets was built in 1950 and has thus existed on Bachubai Eduljee Road for 70 years. Ahmadis have not built many places of worship featuring minarets since a 1974 amendment to the Constitution of Pakistan that declared them non-Muslims.

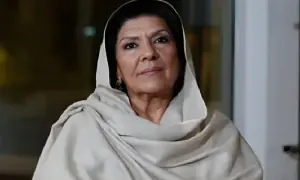

“Let alone building a place of worship with minarets, we are not allowed to construct a simple prayer hall,” Amir Mehmood, a Jamaat-e- Ahmadiyya Pakistan spokesperson told Aaj News.

Spokesman Mehmood said several Ahmadi places of worship were either sealed or taken over from Ahmadis after the 1974 constitutional amendment. The attacks have grown in the past two to three years, he added. Hundreds of Ahmadis have been booked after being accused of “posing as Muslims”, using Islamic epithets, calling the Azan, or offering prayers.

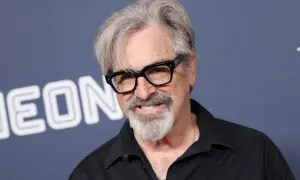

Manzoor Meo, a lawyer who has represented the Khatam-e-Nubuwwat (or the finality of the Prophethood) Movement in several cases, defends such arrests, saying the country’s laws and courts explicitly prohibited Ahmadis from using Muslim rites and rituals — widely known as shaeayir-e-Islam to a majority of Pakistanis.

The removal of minarets at an Ahmaddiya place of worship could be justified because it amounts to taking back possession of what belonged to you in the first place, Manzoor Meo said while speaking to Aaj News.

Is there, however, any law that prohibits Ahmadis from erecting minarets on their places of worship? And if the laws prohibit Ahmadis from using Muslim rites and rituals, then is dismantling them tantamount to taking the law into your hands, when legal recourse is available?

The explanation Meo offered to these questions is rooted in the legal and constitutional history of Pakistan.

Crux of a legal question

The 1974 constitutional amendment defined who could be called a Muslim and who is a non-Muslim. Anyone who does not believe in the finality of the Prophethood of Muhammad (peace be upon Him) is not a Muslim.

The amendment specifically states that “persons of Qadiani group or the Lahori group (who call themselves ‘Ahmadis’)” were non-Muslims.

The amendment itself did not impose explicit restrictions on Ahmadis. It was Ordinance XX of 1984 that prohibited Ahmadis from calling their place of worship a “masjid” and preaching their faith.

Under the “Anti-Islamic Activities of Qadiani Group, Lahore Group and Ahmadis (Prohibition and Punishment) Ordinance 1984” — as it was called — Ahmadis were also forbidden from calling their “mode or form of call to prayers … ‘Azan’. They could not recite the Azan as used by the Muslims.

Although the ordinance, too, did not place an explicit ban on minarets, its many interpretations accepted that minarets and mehrab were also among shaeayir-e-Islam and Ahmadis could not use them. The ordinance was never turned over by a court because it was based on the 1974 amendment, which has far-reaching consequences.

According to the Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya Pakistan spokesperson, a campaign to take over Ahmadi places of worship started soon after the 1974 amendment.

The Ahamaddiya community challenged the 1984 ordinance before the country’s top court. The Supreme Court of Pakistan gave a judgment in 1993, declaring that the ordinance was “well-founded.”

Manzoor Meo says the 1993 Supreme Court judgment made it clear that Ahmadis needed to accept that they were the followers of a particular religion which was not Islam. Their rights as a minority were protected by the law, but they were trying to steal Muslim identity.

In fact, the entire legal debate in the 1990s centered around the question of why any attempt on the part of Ahamadis to follow Muslim rituals and rites was hurtful to the majority faith.

Justice Abdul Qadeer Chaudhary, who wrote the 1993 judgment, attempted to answer the question using the analogy that a company like Coca-Cola would go to every length to protect its brand name and identity. He said Coca-Cola Company would not permit anyone to sell their product in bottles labeled “Coca-Cola”.

Hence, Ahmadis would not be permitted to use Islamic epithets, which belong exclusively to Muslims.

The interpretation of the 1974 amendment and Ordinance XX has wider ramifications.

A case that made headlines was of six minarets of an Ahmadi place of worship, Baitul Hamd, that were demolished in Kharian by the police in July 2012.

In December 2022, the minarets of an Ahmadi place of worship were removed in Gujranwala.

In January 2023, police razed minarets of a place of worship belonging to the Jamaat-e-Ahmadiyya, in Wazirabad, according to a spokesperson of the community.

Why do minarets matter

Mehmood, the Jamaat-e-Ahmaddiya spokesperson, argues that minarets are also found on Hindu temples and churches, so, they were not an architectural feature that is exclusive to one faith.

However, this is not only a question of stopping a community from having minarets simply because of their religious symbolism.

Manzoor Meo argues many of the Ahmadi places of worship were originally set up as mosques and their land was allotted by the government to “Muslims”.

He gave the example of a case involving the control of a mosque before the Lahore High Court. Ahmadis claimed that they had established the mosque in 1863 after acquiring a land lease from the government and that after the 99-year lease expired in 1962, they had every right to have the lease extended in their name.

The only problem, says Meo, was that in 1863, the Ahmadiyya faith did not exist. Mirza Ghulam Ahmed, its founder, was born in 1835 and he declared himself a prophet only in 1889.

The Khatam-e-Nubuwwat Movement claims that many old structures with minarets belonged to Muslims and Ahmadis were illegally occupying them. It is the same as a piece of land allocated for a church by the government should go only to a church, said Meo.

There are similar claims about the two Ahmadi places of worship attacked in Karachi on January 18 and February 2, 2023.

In both cases, police received complaints from people who said Ahmadis had erected minarets to mislead Muslim worshippers to their places so that they could be influenced by Ahmadi preachers.

But it was later submitted to a court that the piece of land at Martin Quarters Road was allotted originally for a mosque, according to a spokesperson of the Khatam-e-Nubuwwat movement.

‘Can they say they built the minarets?’

The FIRs named certain members of the Ahmadiyya community as the management of the two places of worship and demanded that the police arrest them.

No arrests were made. Unlike their counterparts in Punjab, the Sindh police refrained from acting on the complaints.

The place on Martin Road was attacked five months after the complaint was received in August 2022. Similarly, the FIR against the place of worship at Bachubai Eduljee Road was lodged in September 2022.

Spokesman Mehmood says the Ahmadiyya community has filed an application over the attacks.

Lawyer Manzoor Meo believes that no crime was committed when minarets were removed in the two incidents. “What crime was committed? Can they file an FIR saying that they had built the minarets? It [using minarets at Ahmadi places of worship] is against the law,” he said.

On Friday afternoon, police registered an FIR against five individuals. Sindh government spokesperson and former Karachi Administrator Murtaza Wahab tweeted a copy of the FIR, which said the worship place was established before Pakistan came into being in 1947.

Mehmood says the persecution of Ahmadis in Pakistan has a long history. “Ahmadis are not allowed to die peacefully. Their graves are desecrated [to remove everything that is categorized as Muslim],” he said.

The Jamaat-e-Ahmaddiya spokesperson said that in a 2014 ruling, Justice Tassaduq Jilani had issued seven directives to the federal and provincial governments for the protection of religious minorities in Pakistan, ordering the formation of a task force. The government has not formed the task force, let alone implement the judgment, he said.

Lawyer Manzoor Meo, however, cited the 1993 Supreme Court judgment which, he said, made it clear that Ahmadis will enjoy complete religious freedom in Pakistan after they declare their real faith.

For the latest news, follow us on Twitter @Aaj_Urdu. We are also on Facebook, Instagram and YouTube.

Comments are closed on this story.